| nbc home | |

|

PRESS |

"TURKEY CINEMASCOPE" ( Bezesteni Market, 17 Nov 2006 - 3 Dec 2006 )

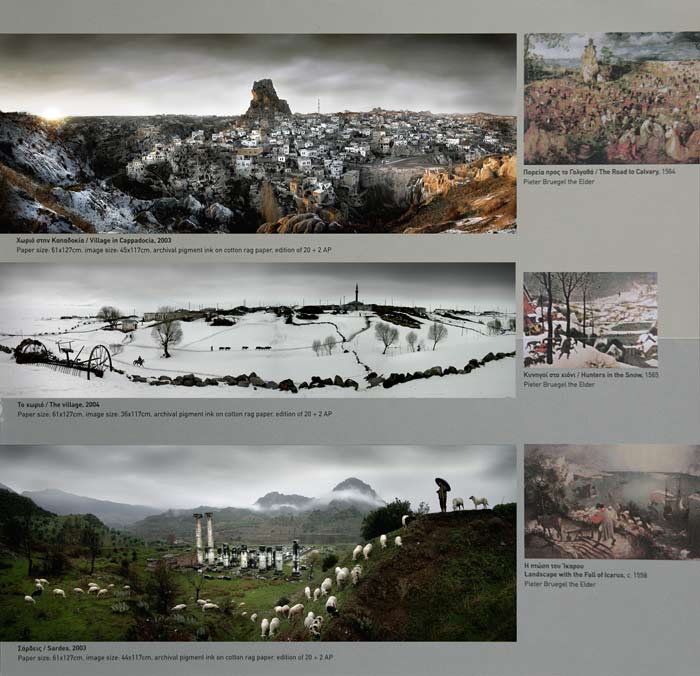

Ronald Bergan, Guardian (UK), 27 November 2006 ........................................................................................................................................................ Geoff Andrew, Time Out (UK), 30 November 2006 ........................................................................................................................................................ Ronald Bergan, Greencine, 29 November 2006 ........................................................................................................................................................ Marion Inglessi, Greece, November 2006 One of the most outstanding characteristics in both Bruegel's and Ceylan's landscapes is the viewer's perspective. The painter and the photographer choose to describe the scene from above, from the top of a

mountain, from a bird's eye view, (or the eye of God observing the earth). Ceylan's photograph Curved Street in Winter is taken from the second storey of a building. There is a curved street in the snow forming a choreographed trajectory, and a series of identical dark-clad figures with downcast eyes, walking oblivious to our scrutiny, as though the same person were duplicated as far as the eye can see. In Bruegel's Hunters in the Snow, we have the same point of view, a similar purpose of movement and body language - the averted faces, the bent backs - the curve of the hill replacing the curve of the road with the depth of field remaining the same. Even the monochromatic quality of both worlds is similar. Furthermore, Ceylan's photographs The Village and Football Players near Mount Ararat could be close-ups of the Hunters painting with a powerful zoom lens. Every minute detail is discernible, down to the faintest trace of movement or life in the vast frozen landscape. The photographs Village in Cappadocia and Ishakpasa have the same layout and outlandish feel to them as Bruegel's paintings The Road to Calvary and The Tower of Babel. Village in Cappadocia is a panoramic photograph from a promontory across a precipice, where a city carved in the rock rises up out of the void. A bare rocky cliff looms over the ashen city, which seems abandoned, petrified, spellbound. Ishakpasa likewise, seems to have materialised in the cradle of the mountains without human intervention, like an imaginary vision, a golden mirage. In Bruegel's two paintings the mood is the same, the heavy skies, the imaginary landscape, the rock-city. It is almost the same film location, first totally bereft of life, then suddenly swarming with activity. In the photograph Sardes, there is a harmonious flow between the creations of man and those of the Universe. The silvery light piercing the clouds, the mountains in the distance, the green hills peppered by the white sheep rolling down the slope. Suddenly, the ruins of a temple spring out of the ground lending a serious note to the lightness of the scene, which finds its climax in the dignified and comical figure of the shepherd perched like a little god on the top right hand side of the photograph holding an umbrella. If the camera sweeps panoramically to the left over the hill, we will find ourselves without effort or surprise in Bruegel's painting Landscape with the Fall of Icarus. The clouds part and the sun shines golden over sea and land. All of nature breathes in unison. The sheep climb over the next cliff, man goes about his daily toil, the ships open their sails to the rising wind, the city glitters in the distance, the sea follows the curve of the horizon, even Icarus, who vanishes in the foreground, barely makes a ripple. The world is too magnificent, and man's passage is transient. Only his creations remain behind - cities, a plowed field, ancient ruins, works of art, paintings, photographs, films...

|