|

The four seasons of life Translated from Greek by Tina Sideris

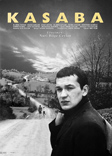

Nuri Bilge Ceylan's The Small Town is a film made with admirable simplicity. Like nature, simple and majestic, like the course of a life, difficult, deterministic, enchanting, adventurous, complex, like death mysterious and inaccessible. The small village of childhood, a miniature of '70s Turkey, is like any other birthplace, both homeland and prison. The film is divided into four acts, one for each season of the year, during which the two young leading characters, seven-year-old Ali and eleven-year-old Hulya, begin an adventure that could be the adventure of a lifetime. The film opens with "Winter", at the snow covered schoolhouse, which is inaccessible for some students, with the boring repetition from the jingoistic primer, faithful to the triptych country-religion-family. A student is late due to the heavy snowfall. When he reaches the room, he takes off his shoes and socks and hangs them on the stove pipe to dry. A girl reads: "Solidarity means believing in one another as regards feelings, interests and thoughts. People cannot live alone and meet their needs. That's why we need one another. We must help the poor as much as we can..." Drops from the boy's wet socks sizzle on the stove top with the characteristic sound of water evaporating on a hot surface. The new generation at the first morning school prayer, in the middle of the snow-covered landscape, swears allegiance to the goals set by Ataturk and "gives up its existence to Turkey". The reasons that make Ceylan speak of solidarity are not political. A lone artist on a completely personal journey exorcises his fears of loneliness in a country that is unique in its relationship to the worldwide community. "Spring" finds the two children in a forest that is blooming and vibrant with life. The father of Ali and Hulya, as he will declare in the next piece, no longer believes in humanity, he only believes in nature. Ceylan's close-ups support this reasoning at every opportunity, adding as a subtext that man himself is part of nature and cannot live removed from it. At first the foliage of the trees, the donkey's eyes, the turtle sticking its head out and later, the wind in the ear of an elderly father, his wrinkled forehead, the eyes of the eldest son behind his myopic glasses, proof of the toil of a lifetime, the smoke curling out the mouth of the rebellious but listless cousin, the mark of earthly habits. In the eyes of young Ali who is waiting for his father's assent to gather more corn for the fire, human hope meets with the call of nature. "Summer", which in duration is half the film, is full of the endless charter of the elders, about their relationships, complaints, their bitterness with life, the cul-de-sacs, death, plans that never materialized, their struggle to make a life for themselves, their lost opportunities, the dreams that went up in smoke, which finally lulls the young protagonists to sleep. However, the world of grown-ups slyly enters the children's dreams and Ali dreams of the turtle he left to die in the forest by turning it on its back. And while the men continue to chatter, the women are overworked and tired. The grandmother thinks that there is nothing in life other than work, which is not an obligation, not a choice, and naturally not pleasure. It is man himself, it is the absolute connection of life on earth with work, it is the mother's instinct that leaves no room for choice. "Fall" at the house, waiting for "Winter", the adventure is incarnated as a coming of age dream. Hulya dreams of her grandfather, dead in the grass, near the stream. The little girl lifts the dead man's white shirt and heads for the stream. She hesitantly dips her hand in the water. Even in her sleep, Hulya wants to "dive" into life. It is amazing how many views of man's existential essence Ceylan manages to display in such a short film. He himself remains an impartial observer. He silently but determi-nately underlines the changes of man in conjunction with the perpetual change of nature's seasons. While all the conversations hold the undeniable truth of each person, all at some point declare their awe of undefeatable nature. The film was shot by a two-man crew! An unbelievable fact in an age where each low budget film needs at least 20 to 30 technicians. Ceylan, with a non-sync, noisy 35mm camera and a tripod, envelops people and records whatever he can from the immediacy of their amateurism. The result, in the context of the Spartan minimalism of his resources, shows a director with absolute clarity of vision, cinematic precision and inspiration, knowledge of the natural world, of light, of facial shadows, the recording of detail and steady, powerful, expressive framing. The achievement of this film is that, in spite of the nonexistent resources with which it was made, it constitutes, in the context of contemporary cinema, a solace for the eyes and the soul. It is a return to pure cinema. A camera, a few people, landscapes and sounds are all Ceylan needs to set up his universe.

|