|

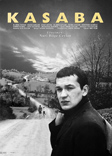

Dialogues with Films : Four Decades of the Forum Jia Zhangke on Kasaba

In 1998, I came to Berlin with my film Xiao Wu (The Pickpocket) and took part in the International Forum of New Cinema at the Berlinale. Xiao Wu was my first feature. I shot it in the tiny village right in the middle of China that I call home, a place cut off from the rest of the world where my entire life was spent until I turned twenty one. The years spent growing up there, the memories of my childhood and adolescence, the way the sand was whirled around by the wind, the trumpet sounding at the same time every day from the far away barracks – I wanted to bring all these things back to life in my film. After I arrived in Berlin, a Turkish film caught my eye that was, like mine, showing in the International Forum of New Cinema. The director was called Nuri Bilge Ceylan and his film Kasaba (The Small Town). I hadn’t the faintest idea of what a Turkish village might look like or how the people there might live. Would they have the same problems as I had? What sort of worries and hardships would they face? What sort of pleasures might they experience? I was full of curiosity as I marched into the auditorium to watch the film. It was only after I’d taken my seat in the auditorium, the light had gone out and the screen had flickered into life that I realised the film was in black and white. The film began with a flurry of snow. The whole sky, as far as the eye could see, was full of swirling snowflakes. How familiar this scene felt to me! The children from a small Turkish village had one thing in common with me: the way a sudden change in the weather is able to inject a fantastic feeling of freshness into an otherwise stagnant life. The laughter and the hoots of the children on their toboggans in that small Turkish village sounded just like the Chinese children back home. One of the children has to go through the mountains to get to school. When the boy finally arrives at class, he takes off his shoes that are wet from the snow and warms himself by the stove. The round iron stove in the classroom gives out heat, through the window you can see out into the cold again. Were these not exactly the same childhood memories I had of winter back home? Then the boy takes off his socks to hang them over the oven. The way the water from the socks drips down on to the stove! The hissing of the steam, it was all so familiar to me. I love Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s film because the language that is important in the film works in an entirely different way to any spoken language, soaring high above them. I only speak broken English and am a long way away from being able to follow subtitles on a screen. But the visual language alone was enough to allow me to look deeply into the heart of the director and to understand his entire way of thinking. I think that Ceylan is even able to describe the climate of a particular area with a great deal of clarity just by using images. The cold that cuts through both bone and marrow after a snowfall and the warm mist that follows it, surrounding the children as they play in the snow. Feet that feel frozen solid in the snow, the water dripping down from the socks, hitting the stove and hissing as it does so. And the moist clouds rising upwards; it is all this that forms the drama of the film. As a director, I don’t think much of individual narrative sequences. For me, it is always the atmosphere that is the decisive factor in a film’s success. I remember hearing that Hou Hsiao Hsien visited Akira Kurosawa while he was still alive. Kurosawa asked his assistants to tell him why they thought he liked Hou Hsiao Hsien’s films. They put forward a whole wealth of different philosophical explanations, but Kurosawa just shook his head and said, “No, that’s all wrong. What I like about his films is the fact that you can see the dust and sand in them.” I think that’s the most special thing about Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s work as a director, he understands how to represent the feelings and the atmosphere that arise from the weather. Another thing that captivates me about his film, that leaves me feeling intoxicated, is the world of sound. Many of the sounds in the film are amplified to an exaggerated degree. He takes sounds from the real world, gleaned from a complex range of different states, and then puts them together and modifies them so as to awaken that feeling of strangeness that we all know so well. It is a feeling of strangeness that generates a sense of the poetic, an enticing strangeness. The sound of drops of water dropping into the flames of the stove and hissing, the noises of the animals in the natural environment, human voices calling for help from afar that sound almost unreal. The twittering of birds, the chirping of crickets, the rustling of the wind, the crash of thunder are all noises that we have become used to just ignoring. Now we encounter them again in the cinema in a highly accentuated way. While I was watching the film, it was as if the long-closed valves of my memory re-opened once again as if by magic, whole years appearing before my inner eye which I would never otherwise have been able to remember and which I had never actually remembered before. I love the microscopic view of the world in Kasaba, the way of looking at the animals, at every tree, at every single blade of grass. It’s like a minimalist form of x-ray vision that takes in all the details, revealing the surface structure, examining the texture of the epidermis. These small things are the very essence of what lies within the living macrocosm, just like we are too. But we have never made the effort to focus our attention on them, to observe them at close range in a thorough, complete manner. The director uses the camera to focus on the things we overlook, natural occurrences that we have always ignored. In reality, he just shows us the parts of ourselves that we’ve neglected to pay any attention to, our subjective feelings. We notice that we have become completely jaded. And we realise that this is because we have never properly listened before, focussed our gaze, shown sensitivity and empathy, actively tried to feel the cosmos we belong to. I believe that Nuri Bilge Ceylan shoots his films according to his sense of touch. When he’s behind the camera to capture a particular scene, you can be sure that he felt the very air beforehand, let himself be stroked by the sun. These are the sensations he carries into his films.

|